If all modern humans originated in Africa and only later migrated around the globe, as theory holds, the paths of our ancestors' wanderings may still be visible in our genes. A new genetic study supports just such a scenario and suggests that early Africans colonized the planet gradually through a series of small migratory steps. Results of the worldwide genetic sampling project show a strong correlation between genetic diversity and geographic distance. The closer modern people live to one another, as measured along the ancient migration routes that led humans out of Africa, the more similar is their DNA.

"Geographic distance is very good at predicting genetic distance. The correlation between the two is very high," said Sohini Ramachandran, an evolutionary biology doctoral candidate at Stanford University. Ramachandran is the lead author of the study, published in today's issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Geneticists have long known that genetic differences between populations increase with physical distance. Groups that live close to one another interact, interbreed, and become more genetically related. The new study adds a more detailed perspective to the concept. It's not simply distance that has helped shape the modern genome, the authors suggest, but the way in which humans migrated over those distances.

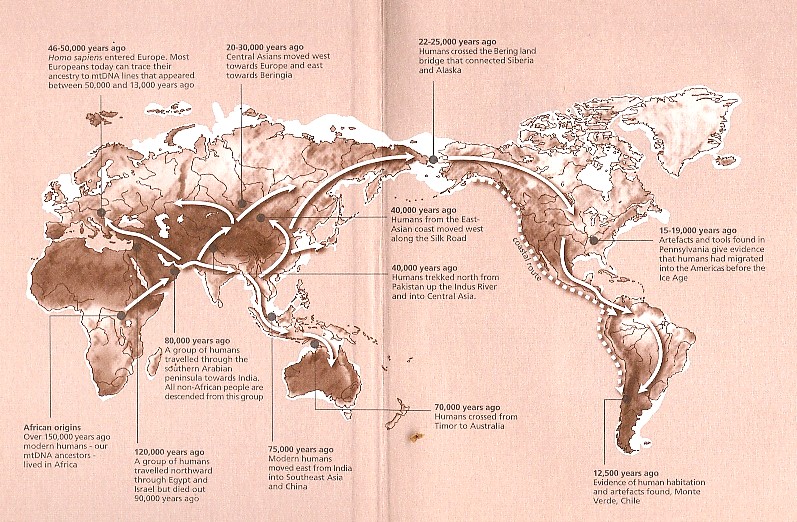

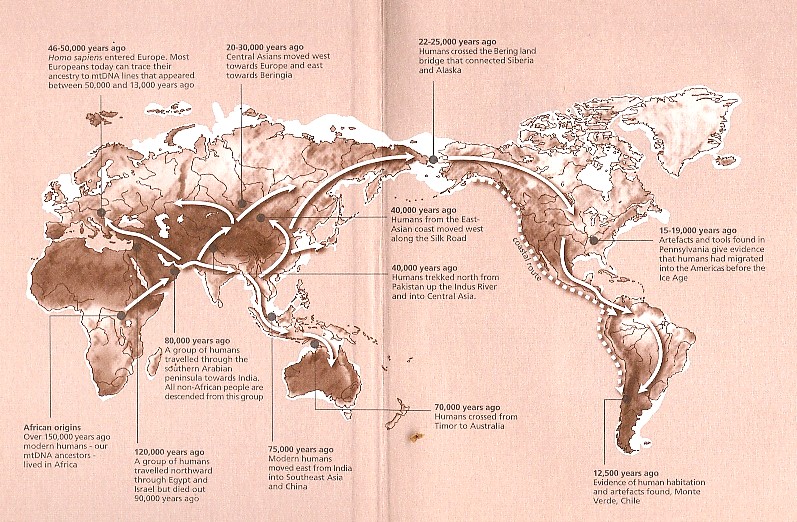

The new data show that genetic diversity decreases as one traces ancient migration routes out of Africa. "There's a very linear decrease of "genetic diversity" as you leave Africa, and it's a bit surprising that it would fit the pattern so well," Ramachandran said. Ramachandran and her colleagues studied the genes of 53 indigenous populations around the world. The researchers selected five key waypoints as the crossroads of ancient human migrations: Cairo, Egypt; Istanbul, Turkey; Cambodia; and the Alaskan and Russian coasts along the Bering Strait. "We tried to figure out what kind of picture of human evolutionary history would explain the high genetic correlation that we observed," said Noah Rosenberg, a University of Michigan geneticist and study co-author.

The team says their research kept pointing back to a single place of human origin: Africa. "When we searched over 4,000 points around the world, we found that no point outside of Africa had as high a fit as any point inside of Africa," Rosenberg said. "So this seems to support an 'Out of Africa' historical model for human evolution." Genetic diversity is highest, and thus oldest, in Africa. This fact has led many geneticists to point to the continent as the birthplace of humankind. Genetic data suggest what scientists call a serial founder effect. The theory holds that each group of migrating humans begat a later, smaller subgroup that subsequently continued humankind's journey around the globe.

Each time a subset migrated onward, genetic diversity narrowed. As a result, naturally occurring random genetic variationsalso known as genetic driftincreasingly influenced the genetic makeup of gradually more homogenous populations. Genetic diversity was found to be lowest in the Americas, which are widely believed to be the last continents settled by humans. The team concludes that perhaps 75 percent of humankind's modern genetic variation is the result of random genetic drift.

The researchers suggest that only 25 percent of our genetic diversity stems from the evolutionary process of natural selection, though such a number is still significant. "Undoubtedly natural selection has played an important role in altering our genome during this migration out of Africa," Ramachandran said. "But it is kind of new to think that genetic drift might have been responsible for this much of human genetic variation."

Mis à jour le 22/03/2025 ![]() pratclif.com

pratclif.com